Full-thickness skin defects caused by burns and trauma can lead to significant functional and aesthetic morbidities. Reconstructive surgery of full-thickness skin defects should achieve optimal results with minimal donor morbidities. Replacing deficient tissues with those that have similar textures can be challenging in such patients. Flaps, which provide the most pliable tissues, are considered the first option in the reconstruction of full-thickness skin defects. When flap options are limited or the patient's general status is not suitable for complex surgery, alternative options, such as artificial dermal templates (ADTs), should be considered.

ADTs, originally designed as an extracellular matrix and skin substitute for extensive burn injuries, are shown to reduce scar contraction.1,2 The indications for using ADTs are to reduce scar formation after skin contracture release, to yield a more elastic scar after traumatic skin defects, to cover full-thickness skin defects, reduce donor area morbidities, and to protect the underlying tissues after tumour resection or complex injuries.2

Several kinds of artificial epidermal and dermal skin templates are commercially available. Each has its own advantages and disadvantages. No specific indication or algorithm to choose between these templates has been reported in the literature, to our knowledge.

In this study, we describe our experience of using an ADT, Pelnac (Gunze Ltd., Japan) for burn contractures and wound coverage.

Method

This retrospective study included patients with trauma and burns requiring scar release or wound coverage who were treated with a single-layer ADT, between May 2017 and May 2019 at the Izmir Bozyaka Education and Research Hospital. Data regarding patient sex, age, type of injury, location of the injury, comorbidities, operations and complications were recorded. Patients who had at least a one-year follow-up were included in the study; patients who were lost to follow-up before one year were excluded. The Vancouver Scar Scale (VSS) was used in patients to assess the final scars.

Ethical approval and patient consent

All procedures performed in this study were in accordance with the ethical standards of the local institutional research committee, and with the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. All participants signed a written informed consent form to take part in the study, and gave written permission to publish their photographs.

Results

The single-layer ADT was used in 24 patients. Patient characteristics are summarised in Table 1. Location of use of the ADT included: the upper extremities (n=9), the head and neck region (n=8), lower extremities (n=4) and torso (n=3). The indications for using the ADT were:

- Releasing burn scar contractures

- Permanent wound coverage for acute traumatic wounds with exposed tendon or bone

- Temporary wound coverage for patients requiring complex reconstructions.

Table 1. Patient characteristics Patient

| Patient | Age, years | Sex | Aetiology | Examination | Comorbidity | Operation | Outcome | Complication management | VSS–Preop | VSS–Postop | Follow-up |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 37 | F | Burn | Frontal, bilateral eyelid, cheek, perioral contracture | – | Full face contracture release, Pelnac + STSG | Insufficient release | Multiple sessions of regrafting, Z-plasties, fat injections | 11 | 8 | 36 months |

| 2 | 37 | F | Burn | Bilateral total hand contracture | – | Finger and hand dorsum contracture release, Pelnac + STSG | Insufficient release | Patient refused further operations | 12 | 9 | 30 months |

| 3 | 21 | F | Burn | 2. 3. 4. 5. Finger volar contracture | – | Finger contracture release, Pelnac + STSG | 5. finger insufficient release | STSG | 11 | 6 | 20 months |

| 4 | 33 | F | Burn | Anterior neck contracture | – | Neck contracture release, Pelnac + STSG | Insufficient release | Patient refused further operations | 11 | 9 | 20 months |

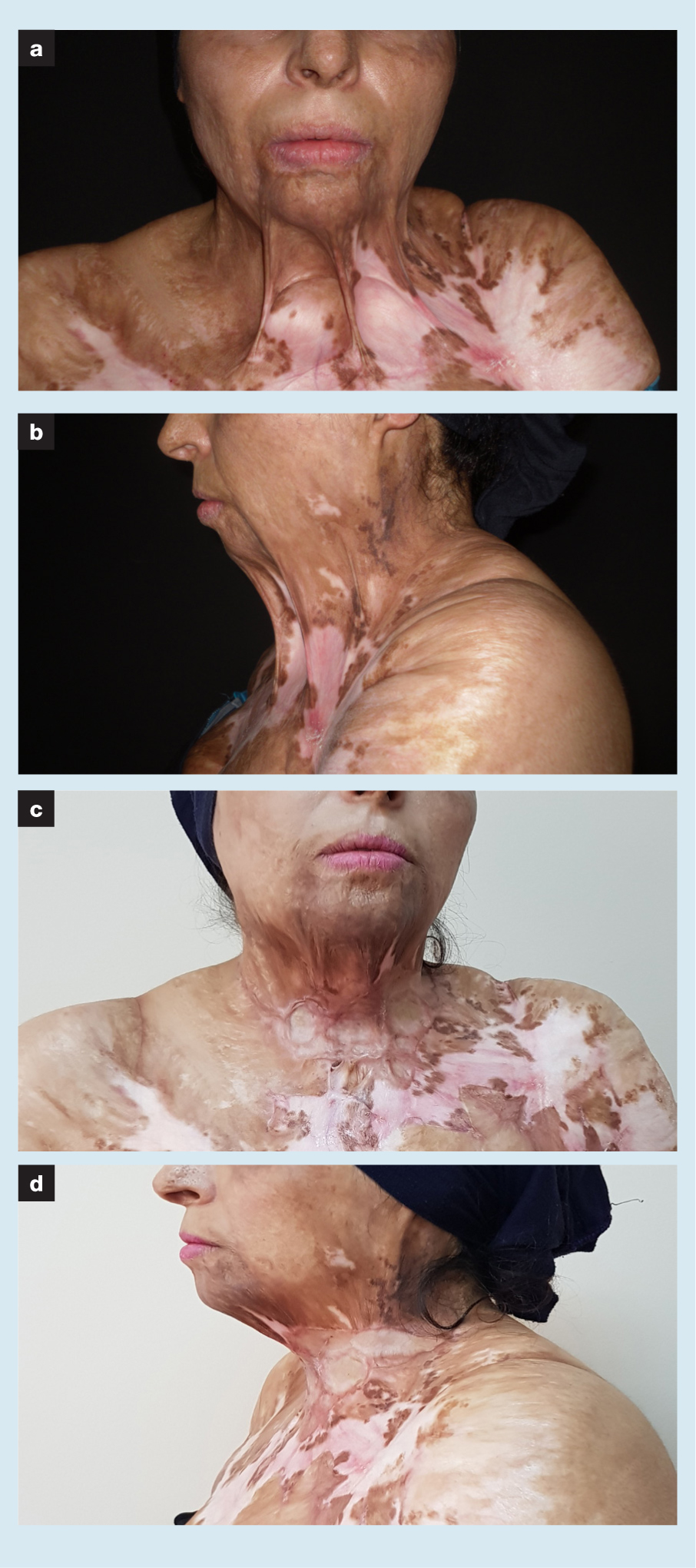

| 5 | 26 | F | Burn | Anterior neck contracture | – | Neck contracture release, Pelnac + STSG | Insufficient release | Patient refused further operations | 11 | 8 | 25 months |

| 6 | 61 | M | Burn | 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. Finger volar contracture | DM, HT | Finger contracture release, Pelnac + STSG | Successful release | – | 11 | 4 | 15 months |

| 7 | 27 | M | Burn | 2. 3. 4. 5. Finger volar contracture | – | Finger contracture release, Pelnac + STSG | 4. 5. finger insufficient release | Interpolation abdominal flap | 10 | 7 | 20 months |

| 8 | 62 | F | Burn | Anterior neck contracture | DM, HT | Neck contracture release, Pelnac + STSG | Insufficient release | Freestyle perforator island flap | 13 | 9 | 12 months |

| 9 | 23 | M | Burn | Elbow contracture | – | Elbow contracture release, Pelnac + STSG | Insufficient release | Interpolation abdominal flap | 13 | 10 | 13 months |

| 10 | 75 | F | Burn | Medial breast keloid | DM | Scar release Pelnac + Z-plasty | Successful release, diminished pain | – | 12 | 4 | 15 months |

| 11 | 66 | F | Burn | Lateral breast scar with bone adhesion | – | Scar release Pelnac + Z-plasty | Successful release, diminished pain | – | 10 | 4 | 12 months |

| 12 | 58 | F | Burn | Inguinal scar contracture | – | Scar release Pelnac + Z-plasty | Successful release, diminished pain | – | 9 | 4 | 14 months |

| 13 | 27 | M | Trauma | 5×3cm tendon exposed gunshot wound | – | Debridement, STSG + Pelnac | Exposed tendon at 3 months postoperative | Posterior tibial perforator flap | – | – | 36 months |

| 14 | 50 | M | Trauma | 2×2cm knee, ankle and tibia defect due to fall from height | DM, PAD | Debridement, STSG + Pelnac | Graft failure | Patient's status not eligible for further operation | – | – | 15 months |

| 15 | 23 | M | Burn | 3×2cm tendon exposed wrist defect | – | Debridement, STSG + Pelnac | Wrist contracture | Interpolation abdominal flap | – | – | 12 months |

| 16 | 65 | M | Trauma | 3×2cm frontal defect due to vehicle accident | – | Debridement, STSG + Pelnac | Successful coverage | – | – | – | 20 months |

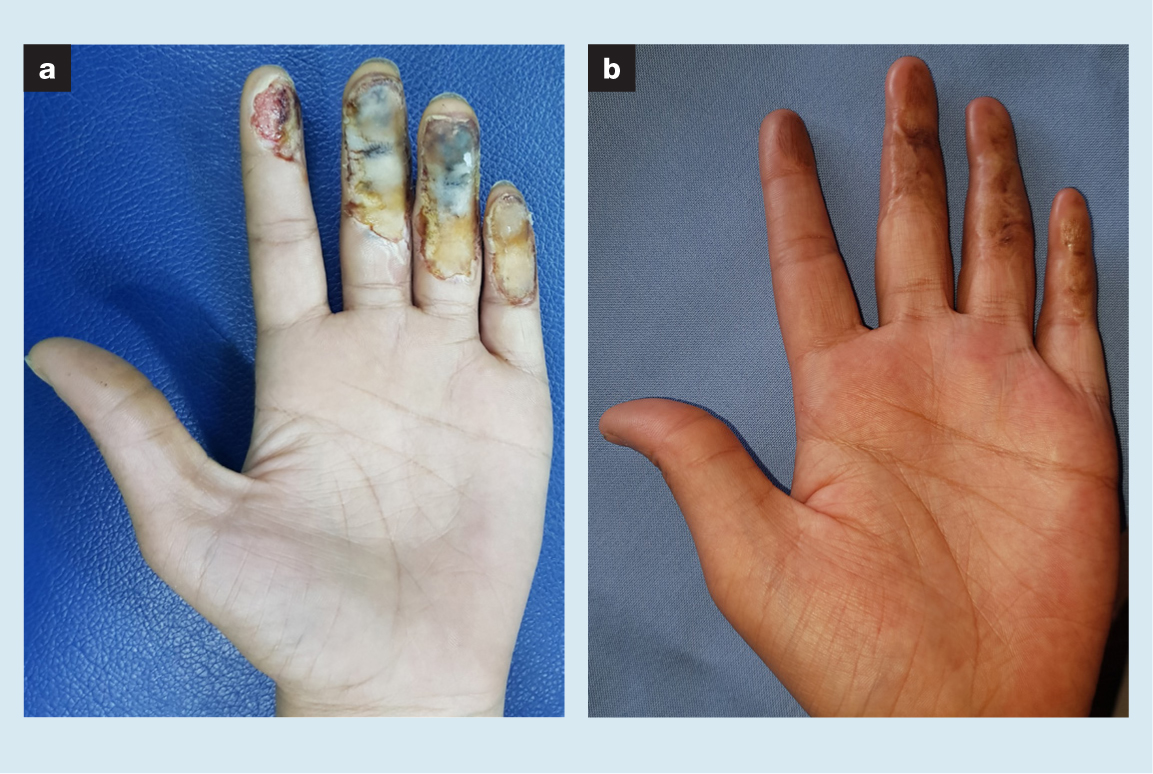

| 17 | 20 | F | Burn | 2. 3. 4. 5. Finger volar side burn with exposed tendon and bone | – | Debridement, STSG + Pelnac | Successful coverage | – | – | – | 16 months |

| 18 | 37 | M | Trauma | 4×3cm hand dorsum crush wound due to occupational injury | DM | Debridement, STSG + Pelnac | Tendon adhesion | Tenolysis | – | – | 24 months |

| 19 | 57 | M | Trauma | 7×4cm anterior tibial defect with exposed tendon and hardware | – | Debridement + Pelnac | Successful second stage reconstruction with anterolateral thigh free flap | – | – | – | 12 months |

| 20 | 57 | M | Trauma | Degloving injury of hand with exposed 5. Metacarpal bone | – | Debridement + Pelnac | Successful second stage reconstruction with STSG | – | – | – | 14 months |

| 21 | 36 | M | Burn | Midfoot amputation defect with exposed tendon | – | Debridement + Pelnac | Successful second stage reconstruction with STSG | – | – | – | 14 months |

| 22 | 63 | M | Basal cell carcinoma | 10×8cm cheek defect with exposed fascial nerve | DM | Tumour excision + Pelnac | Successful second stage reconstruction with radial forearm free flap | – | – | – | 15 months |

| 23 | 71 | M | Squamous cell carcinoma | 12×10cm cheek defect with exposed maxilla and nasal bone | – | Tumour excision + Pelnac | Successful second stage reconstruction with radial forearm free flap | – | – | – | 36 months |

| 24 | 92 | F | Malignant melanoma | 5×5cm defect with exposed maxilla and nasal bone | – | Tumour excision + Pelnac | Successful second stage reconstruction with forehead flap | – | – | – | 12 months |

VSS–Vancouver Scar Scale; F–female; M–male; DM–diabetes mellitus; HT–hypertension; STSG–split thickness skin graft; Preop–preoperative; Postop–postoperative

Releasing burn scar contractures

The ADT was used in 12 patients who were operated on for burn contractures. In nine patients, the ADT was used with split-thickness skin grafts (STSG) in a single-stage procedure. Contractures were released and a single-layer ADT was applied on the defect. An STSG was then applied over the ADT, and the patient was given a bolster dressing for one week.

In three patients, the skin contracture bands were excised and the defects were reconstructed with Z-plasties. The ADT was used under the suture lines to prevent adhesion of the scar to the underlying structures.

Revision surgeries were required in eight patients who had undergone STSG with ADT (Table 1, Figs 1, 2 and 3), whereas none of the patients reconstructed with Z-plasties had additional surgeries. There were no haematomas or infections observed postoperatively. Patients with extremity contractures were referred to physical therapy after two weeks. The VSS revealed an average decrease from 11.6 to 6.8 after the one-year follow-up. All patients with painful contractures reported reduced pain.

Permanent wound coverage for acute traumatic wounds with exposed tendon or bone

In patients (n=6) who were not eligible for complex reconstructions, such as free flaps, and who had not consented to lengthy surgeries, we used the single-stage ADT and STSG. In patients who had exposed bone and/or tendon, the size of the structures devoid of periosteum or paratenon was within 2×2cm.

Preoperatively, we performed serial debridements for all patients and wound cultures were obtained. After adequate debridement was performed and a clean wound was obtained, a single-layer ADT was applied on the defect and an STSG was then applied over the ADT.

Patients were followed up with occlusive dressings for five days, after which dressings were changed every other day for two weeks. No haematomas or infections were observed after applying the ADTs. Patients were referred to physical therapy after two weeks. The grafts had fully taken in two patients without any complications, whereas four patients required secondary operations (Table 1, Fig 4).

Temporary wound coverage for patients requiring complex reconstructions

ADT was used as a dressing to protect vital structures in patients (n=6):

- With wounds that had exposed tendon or bone and who required complex reconstructions but their general status was not stable enough for long operation times

- Who had oncological resections and histopathological examination was required prior to covering the defect.

A single ADT was used in each patient. If there was no discharge on the dressing, the dressing was kept closed for five days, and then changed daily. All patients were successfully operated with flaps after stabilisation of their general status, had tumour-free margins in histopathological examination, and no necrosis or infection was seen on follow-up (Table 1, Fig 5).

Discussion

Trauma and burn injuries with full-thickness skin defects often require reconstructive surgery. Keeping in mind the reconstructive ladder, most defects require skin grafts, and local or distant flaps. Skin grafts alone are not adequate for exposed bone, tendon or hardware. Moreover, owing to insufficient dermal tissue, hypertrophic scarring and contractures can be seen in skin-grafted wounds.3 In patients with extensive injuries for whom no flap options are available or who have other comorbidities that prevent surgery, local and distant flaps are not suitable. However, in patients with extensive injuries or oncological patients in whom reconstructive surgery is postponed, exposed bones, tendons, or vital structures are prone to necrosis. In these conditions, ADTs are considered.

ADTs have a wide range of clinical indications. In addition to burn injuries and traumatic wounds,4,5,6 successful and durable results are presented in the literature, especially in wounds due to systemic conditions,7 diabetic foot ulcers,8 degloving wounds of the extremities,3,9 complex oncological defects,10,11,12 and severe traumatic wounds and congenital defects in paediatric patients.13 These templates have also found their place in the reconstructive ladder.14

ADTs are a heterogeneous group, consisting of collagen and glycosaminoglycan or hyaluronic acid. They have different biological and physiological properties, with different thicknesses. These ADTs can be applied to the wound either in one-step or two-step procedures. Usually, these ADTs are laid on the defect, and after 14–21 days of vascularisation, skin grafts are applied on the defect as a part of a two-step procedure. Thinner ADTs, without any kind of sheeting, can be used in a one-step procedure; skin grafts can be covered, together with the ADT. The single-step procedure has an obvious advantage of only requiring one visit to the operating theatre. However, a thin template results with a thin reconstructed skin, which is its disadvantage.15

We used a single-step procedure in our patients with a single layer ADT. This product has both a standard type, consisting of a collagen sponge and a silicone film, and a single layer type, which only consists the collagen sponge. The 3mm collagen layer is a freeze-dried sponge layer made of atelocollagen type 1 derived from porcine tendon. The material is 80–95% porous, with pore sizes ranging from to 70–110µm.16 The entire width of a single-layer, thin collagen sponge is migrated by cells in three days,16 allowing simultaneous skin grafting without significant graft loss.

There are several ex vivo and in vivo animal studies comparing different ADTs. Philandrianos et al.15 reported no long-term differences in scar qualities after six months between five different ADTs. Moreover, there were no differences between patients with ADTs and those in the control group, in whom no ADT was used.

Although the results are of interest, the outcomes can be different in clinical practice. In animals, rapid wound healing, contraction rates, the rapid growth of animals, and difficulties in stabilising the wound lead to different results compared with human subjects.2

Another study compared three different ADTs, including the ADT used in our study.2 Between the tested templates, single-layer Pelnac was shown to have the most contraction. Similarly, single-layer Pelnac has higher contraction rates than bilayered silicone-sheeted Pelnac.16 As Hori et al. stated in their study, further in vivo human studies are required to form an algorithm to use different kinds of ADTs for different indications. These indications should not be based on preference but on their biological properties. In addition, the economic burden of these templates should be kept in mind; a detailed cost assessment is required for decision-making.2

A systematic literature analysis of several randomised controlled studies revealed varied results. Widjaja et al. concluded that there was no evidence that ADTs have a significant impact on scar quality in humans.17 Hicks et al. reported improved mobility and scar quality with the use of ADTs.18 Both studies similarly emphasised that studies in human subjects were variable in methodology and had a small sample size.

In our study, we have used the ADT, in a single stage with skin grafts, in patients requiring burn contracture release and/or who have traumatic wounds. We observed only one case of graft failure but high complication rates related to insufficient contracture releases requiring revision surgeries.

Favourable outcomes, such as a good postoperative range of motion, and patient and surgeon satisfaction, were reported in contracture release patients in the literature.19,20 The complication rates were higher in our study than in the existing literature, and this can be attributed to the type of ADT used because there were no haematomas or infections in our patients, and the postoperative dressings, as well as follow-up protocols, were similar to those in the literature. This particular substitute allows graft take but due to its high contraction rates compared with the bilayered version of the ADT used in this study and with other brands, high complication rates were experienced.

However, when we used these substitutes for temporary wound coverage or for preparing the wound for further complex reconstructive surgery instead of use in contractures, we had better results. In acute wounds, where early reconstruction affects the overall results, ADTs gave us increased flexibility to plan the timing of the reconstruction. In oncological patients, as stated by Rehim et al., using ADTs over the defect while waiting for definitive histopathological examination could turn out to be the only reconstruction required.21

A variety of ADT options are available. We chose this template because of the product's availability and low cost. However, one product cannot produce successful results in all patients. Different types of ADTs may yield better outcomes in different indications.

In the light of our experience, we have limited the use of this ADT in our practice. We use the ADT for temporary wound coverage to protect bone, tendons and vital structures in oncological cases while waiting for definitive histopathological results or to prepare trauma patients for reconstructive surgery. For scar contractures or wounds with exposed vital structures, other types of ADTs, either single-stage or two-stage, are being considered.

Limitations

The limitations of our study are its retrospective nature, the low number of patients, and the use of a single type of ADT. Surgery types, indications and patients could not be standardised.

Conclusion

In select patients, ADTs may have a positive effect on postoperative outcomes, but further comprehensive and comparative clinical studies are warranted.

Reflective questions

- What are the indications for using artifical dermal templates (ADTs)?

- Why do different ADT brands yield different results?

- Why do the results of animal experiments differ from clinical practice in ADT studies?

- Why is a single type of ADT not sufficient to treat all the indications?