Hard-to-heal wounds are commonly defined as wounds that ‘fail to proceed through an orderly and timely process to produce anatomic and functional integrity’1 and include foot ulcers, legs ulcers, pressure ulcers (PUs), open trauma and surgical wounds.2 Despite the varied estimation of epidemiological prevalence, hard-to-heal wounds have been reported to be a growing health problem worldwide during the past decades. In developed countries, hard-to-heal wounds have been estimated to affect 1–2% of the population during their lifetime.3,4,5

Most research in China has focused on hospitalised patients, reporting a point prevalence of 0.15–0.5%.6,7,8,9 The causes of hard-to-heal wounds are complicated, and include trauma, pressure, diabetes, infection and peripheral vascular diseases.10,11 With the development of society and the economy, the main causes of hard-to-heal wounds have shifted from traumatic factors to non-traumatic factors in China. Epidemiological studies have shown that the leading causes of hard-to-heal dermal ulcers changed from trauma and infection in 1995 to diabetes and trauma in 2007.6,7 Research in 2018 reported that pressure and diabetic ulcers accounted for most hard-to-heal wounds in both hospital- and community-based populations.9

The high prevalence of hard-to-heal wounds has resulted in a heavy economic burden, which is rapidly increasing worldwide. It was claimed that $25 billion USD was spent on the treatment of hard-to-heal wounds in the US in 2007.12 Care for hard-to-heal wounds accounted for 22–50% of total community nursing time in Australia and the UK in 2011, which represented a huge burden to medical staff.3 In China, the median cost of care for patients with and without hard-to-heal wounds was ¥6500.18 and ¥3337.16 each, respectively, in 2018.9 With the growing prevalence and extent of hard-to-heal wounds, more accurately planned management is required for both public health agencies and hospitals.

Given the increasing prevalence of multimorbidity in many countries, understanding the role of comorbidity in wound healing is one of the most significant challenges faced by researchers.14 The contribution of underlying diseases notwithstanding, comorbid conditions such as diabetes, malnutrition, peripheral arterial or venous disease, paralysis etc. affect the strategy of wound management.15,16 Coexisting medical conditions make clinical care of wounds more complicated. A clinical practitioner may face the dilemma that treatments of a variety of comorbidities in one patient conflict with each other. The healing time of hard-to-heal wounds varies depending on the heterogeneity of patients, with median time-to-heal ranging from 28–100 days.17,18 During the long period of treatment, individuals with hard-to-heal wounds suffer from the direct effects of wounds, and associated issues such as pain, odour or social isolation, which can in turn aggravate the situation.15 Multiple methods have been applied in clinical practice for improvement of the healing rate, including new wound dressings, updated care concepts, skin substitutes, growth factors, hyperbaric oxygen and negative pressure wound therapy.15,19 Decisions should be made based on evidence and data analysis. However, patients with significant comorbid conditions have often been excluded from randomised controlled trials concerning wound care. It has also been noted that multivariate, risk-stratified analyses based on easily obtainable clinical variables were ‘frequently feasible, but rarely performed’.20 Nonetheless, there is a small amount of data on the prevalence of hard-to-heal wounds with comorbidity aggregations as well as correlation with outcome in China. Despite the aetiological statistics provided, we believe that it is of great value to have regular retrospective analysis and thus facilitate the development of a comprehensive management plan for hard-to-heal wounds.

In addition to the complicated comorbidities, there were thought to be other reasons affecting the interpretation of hard-to-heal wound management. Lacking high-quality, large-scale follow-up data was believed to be one vital cause which resulted in a highly heterogenous strategy of treatment.21,22,23,24 In our study, we developed an online database, the ‘Chinese WoundCareLog’, for multicentre follow-up.25 As per the design of our database, systemic conditions, especially comorbidities such as diabetes, hypertension and infection, should be taken into consideration when hypoglycaemic agents, antihypertensive drugs and antibiotics are prescribed. In this study, we systematically collected and analysed the medical records of hard-to-heal wound cases extracted from the Chinese WoundCareLog database. Based on the large-scale data, we aimed to investigate the characteristics of comorbidities in patients with hard-to-heal wounds, especially the prognostic impact of comorbidities on wound healing. We believed it would provide informative guidance on the current management of hard-to-heal wounds.

Method

Ethical approval

This study was approved and monitored by the Institutional Review Board (IRB) of Ruijin Hospital, School of Medicine, Shanghai Jiao Tong University (2019, IRB Number 95). Informed consent was obtained from patients or their guardians before data collection. Participants' personal details were well concealed and no clinical photographs or case details are included in this manuscript.

This study was registered on the Chinese Clinical Trial Registry (https://www.chictr.org.cn) with registration number ChiCTR1900026682.

Study design

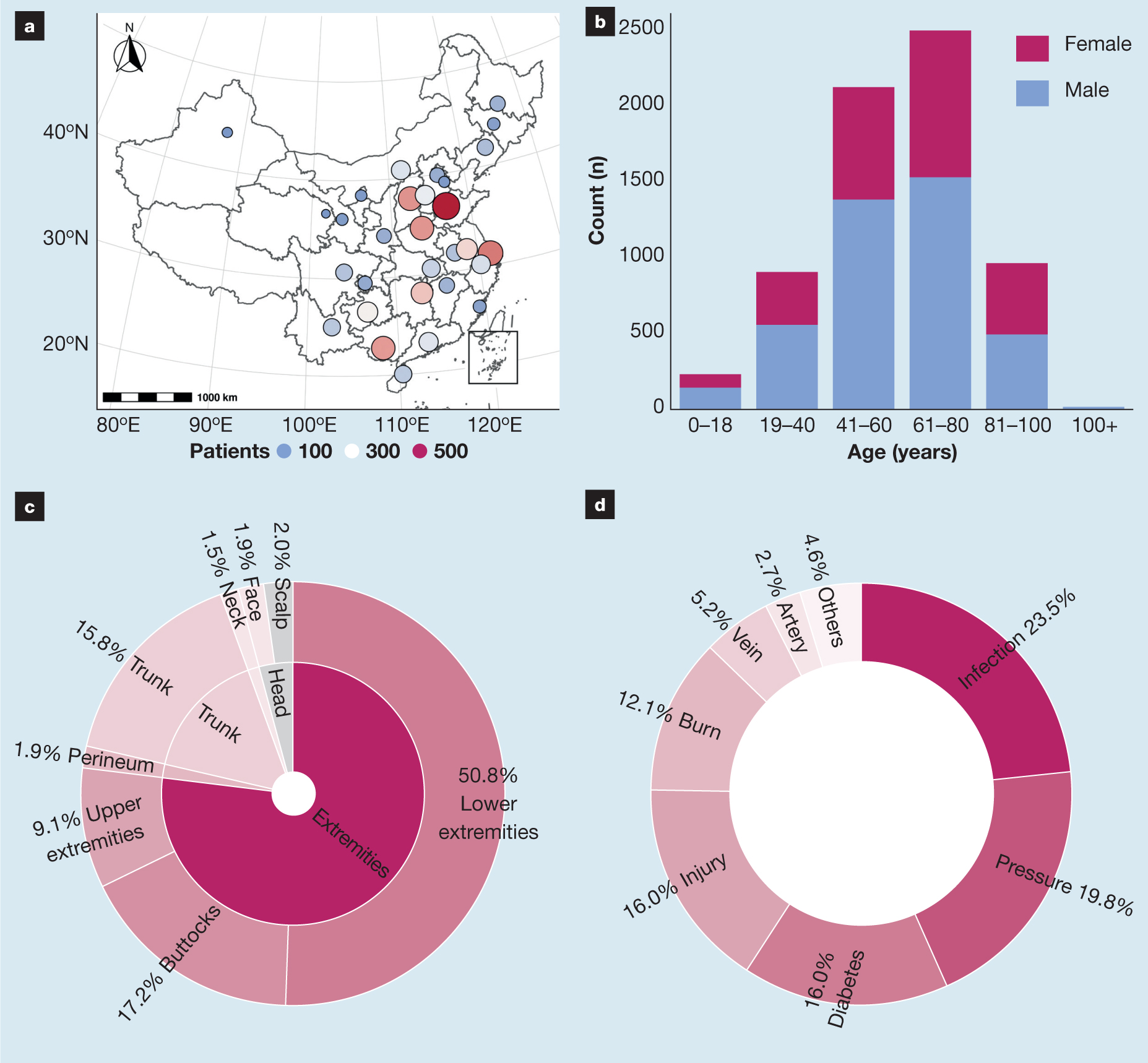

This was a multicentre, retrospective, real-world cohort study. Patients were recruited from the Chinese WoundCareLog database, including both inpatients and outpatients from 522 medical centres nationwide between 8 January 2018 and 31 October 2020 (Fig 1a). All the patients enrolled in this study were diagnosed as having hard-to-heal wounds by professional doctors according to the criteria that wounds remained present for >30 days.26,27 Clinical manifestations, laboratory tests or biopsy findings contributed to the final diagnosis. The exclusion criteria were:

- Serious health conditions that were life-threatening

- Current use of medication that prolonged wound healing, such as sorafenib or glucocorticoids

- Women who were pregnant or lactating

- Episodes of psychosis and/or mental illness

- Refusal to sign informed consent.

For further research on the time of wound healing, patients were excluded from this study if at least one of the following criteria were met:

- Wound was caused by trauma, such as burn or injury, regardless of trauma severity

- Informed consent for follow-up was not obtained

- Further assessment was not available after first visit

- Unexpected intervention or newly developed disease arose during treatment.

The primary endpoint of our study was the complete closure of the hard-to-heal wound. The follow-up time was set to 90 days, which was also the secondary endpoint of our study. The clinical outcomes of wounds were categorised into three groups:

- Healed: complete closure or 75% reduction in volume/area of wound within 90 days follow-up

- Not healed: failure to achieve the status ‘healed’

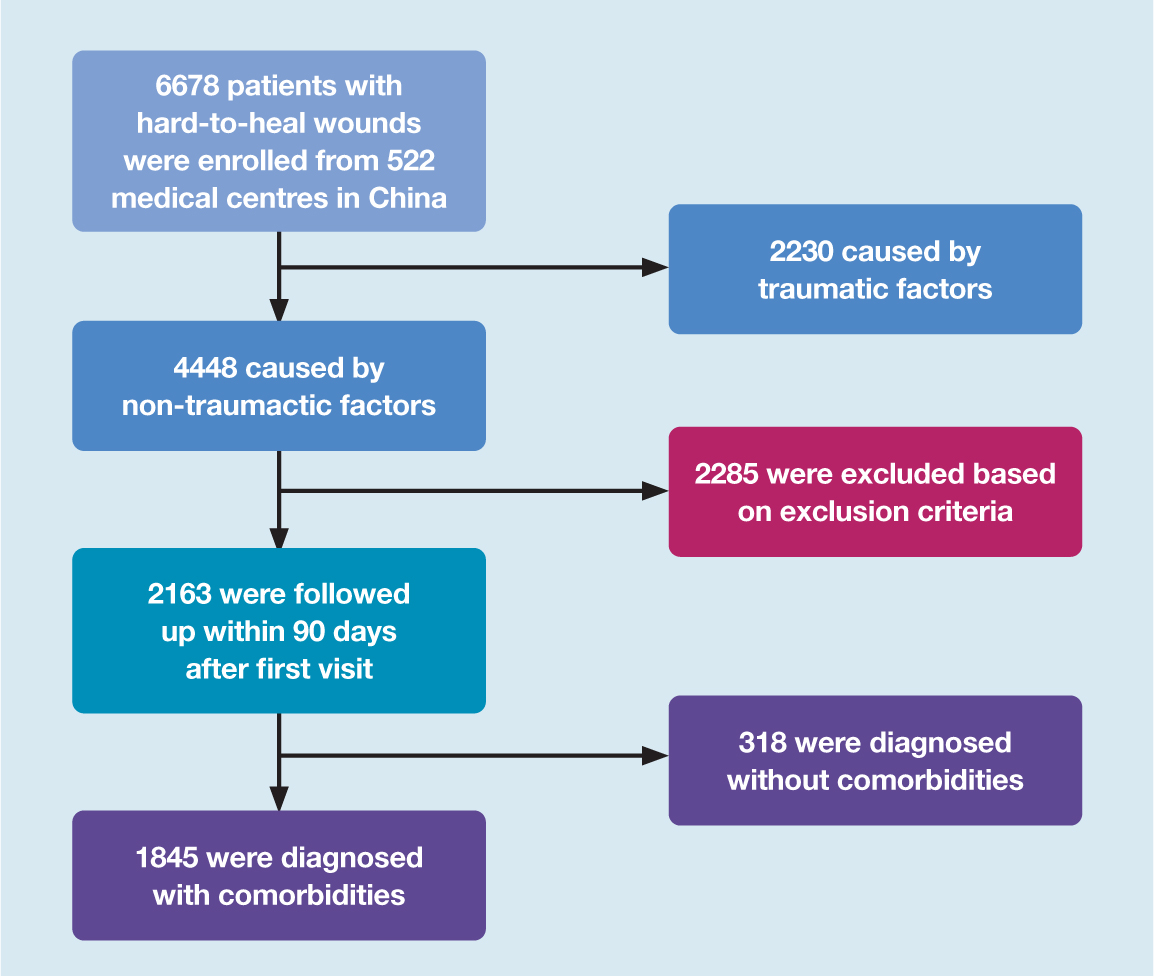

- Drop out: patient withdrawal or loss to follow-up. The study procedure is shown in Fig 2.

Data collection and definitions

Medical records of patients were collected and reviewed by trained doctors, to extract demographic data, clinical comorbidities, treatment process and wound outcomes. Moreover, patients with informed consent to further follow-up were assessed by doctors within 90 days from the first visit. All cases in this study were anonymised to guarantee the privacy of patients. Aetiological classification of hard-to-heal wounds, including typical wounds (diabetes, pressure, peripheral vascular disease) and atypical wounds (malignancy, infection), were determined based on previous studies.8,28 Comorbidities were assessed and classified according to International Classification of Diseases (ICD-10, version 2016 codes).29

Patients with non-traumatic hard-to-heal wounds were included in further analysis, where the wounds were regularly assessed via remote, inpatient or outpatient consultation within 90 days of the first visit to hospital. Treatment process, time and clinical outcomes were recorded by researchers. Considering the feasibility and cost of the study, we set the follow-up time at 90 days. A classification of outcome was given based on the condition of the wound at the end of follow-up.

Statistical analysis

Patient demographic data were descriptive and presented as mean±standard deviation (SD). Prevalence rates were shown with 95% confidence intervals (CI), which were calculated using the Wilson method. To test the differences between patients with or without comorbidities, we used independent sample t-tests and Chi-squared analysis with a significance level of α=0.05. The Cox proportional hazard model for healing rate was applied to identify the relationship between time and wound healing. The Kaplan–Meier curve (log-rank test) was employed to visualise healing differences between comorbidity groups. A two-tailed p-value of <0.05 was considered significant. The R statistical software (version 4.0.0, R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Austria) with ‘survival’ and ‘pheatmap’ packages was employed to perform statistical analyses and heatmaps.30,31

Results

Demographic features

A total of 6678 cases of hard-to-heal cutaneous wounds were included in this study from 8 January 2018 to 31 October 2020. As shown in Table 1, 4931 cases were diagnosed with comorbidities, accounting for 73.8% of the total. The age of patients ranged from 1–107 years (59.1±19.7 years) and the distribution of age showed significant differences between patients with or without comorbidities. The mean age of patients with comorbidities compared with those without was higher (64.0 versus 16.9 years, respectively) while the SD of the age of patients without comorbidities was larger compared with those with (20.4 versus 16.9 years, respectively). The 61–80-years age group had the largest proportion of patients with comorbidities, and the 41–60-years age group had the largest proportion of patients without comorbidities. Male patients accounted for 60.8% of all cases, while female patients accounted for 39.2% (Fig 1b). Interestingly, the sex distribution related with comorbidities demonstrated significant difference and male patients with comorbidities comprised 45.5% of all cases (p=0.01192, Pearson's Chi-squared test with Yates's continuity correction).

Table 1. Characteristics of 6678 subjects with hard-to-heal wounds

| Characteristics | Total | With comorbidities | Without comorbidities |

|---|---|---|---|

| Count (n) | 6678 (100.0%) | 4931 (73.8%) | 1747 (26.2%) |

| Type of Case | |||

| Non-traumatic | 4448 (66.6%) | 3692 (55.3%) | 756 (11.3%) |

| Traumatic | 2230 (33.4%) | 1239 (18.6%) | 991 (14.8%) |

| Gender | |||

| Female | 2620 (39.2%) | 1890 (28.3%) | 730 (10.9%) |

| Male | 4058 (60.8%) | 3041 (45.5%) | 1017 (15.2%) |

| Age (years) | |||

| Mean | 59.1±19.7 | 64.0±16.9 | 45.2±20.4 |

| 0–18 | 234 (3.5%) | 53 (0.8%) | 181 (2.7%) |

| 19–40 | 900 (13.5%) | 387 (5.8%) | 513 (7.7%) |

| 41–60 | 2112 (31.6%) | 1471 (22.0%) | 641 (9.6%) |

| 61–80 | 2470 (37.0%) | 2127 (31.9%) | 343 (5.1%) |

| 81–100 | 958 (14.3%) | 889 (13.3%) | 69 (1.0%) |

| 100+ | 4 (0.1%) | 4 (0.1%) | 0 (0.0%) |

| Wound count (n) | |||

| Total | 7396 (100.0%) | 5450 (73.7%) | 1946 (26.3%) |

| Head | 288 (3.9%) | 137 (1.9%) | 151 (2.0%) |

| Neck | 109 (1.5%) | 67 (0.9%) | 42 (0.6%) |

| Trunk | 1166 (15.8%) | 804 (10.9%) | 362 (4.9%) |

| Perineum | 137 (1.9%) | 102 (1.4%) | 35 (0.5%) |

| Extremities | 5696 (77.0%) | 4340 (58.7%) | 1356 (18.3%) |

Wound position

Hard-to-heal wounds were most commonly located in the extremities, especially the lower extremities, which accounted for 50.8% of wounds (Fig 1c). Patients with at least one comorbidity showed significantly increased incidence of wounds in the extremities (p<0.05), and decreased incidence of wounds in the head (p<0.05) and neck (p=0.004) compared with others.

Aetiological classification

The leading causes of hard-to-heal wounds in this study were: infection (23.5%); pressure (19.8%); diabetes (16.0%); injury (16.0%); burn (12.1%); venous (5.2%); and arterial diseases (2.7%) (Fig 1d). Traumatic wounds, including injury-related and burn-related wounds, accounted for 33.4% of all cases. Patients with comorbidities were significantly associated with non-traumatic causes compared with those without comorbidities (p<0.001).

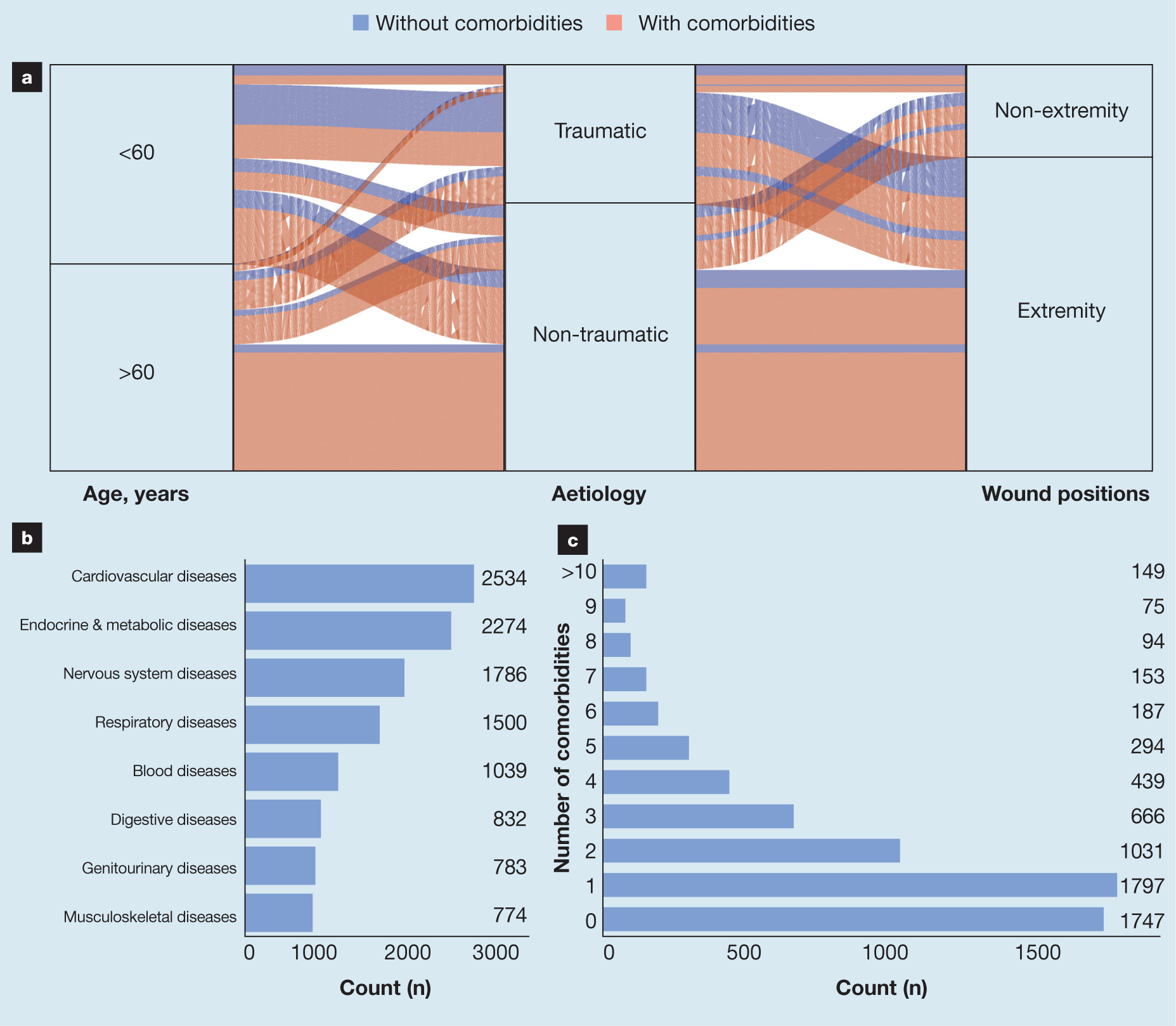

Comorbidity proportion

The prevalence of pre-existing comorbidities classified according to ICD-10 is described in Table 2 and Fig 3b. Most patients had cardiovascular diseases (37.9%), followed by: endocrine and metabolic diseases (34.1%); nervous system diseases (26.7%); musculoskeletal diseases (22.5%); respiratory diseases (15.6%); digestive diseases (12.5%); genitourinary diseases (11.7%); and blood diseases (11.6%). The most prominent comorbidities were: diabetes (28.7%); hypertension (23.10%); cerebrovascular diseases (13.7%); coronary heart disease (10.9%); paralysis (6.9%); fracture (6.3%); peripheral arterial diseases (5.2%); and peripheral venous diseases (4.7%) (Table 3).

Table 2. Distribution of age and comorbidities in 6678 patients with hard-to-heal wounds

| Comorbidities, n (%) | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | >4 | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age 0–18 years | 181 (2.7%) | 34 (0.5%) | 16 (0.2%) | 2 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 1 (0.0%) | 234 (3.5%) |

| Age 19–40 years | 513 (7.7%) | 225 (3.4%) | 71 (1.1%) | 39 (0.6%) | 20 (0.3%) | 32 (0.5%) | 900 (13.5%) |

| Age 41–60 years | 641 (9.6%) | 656 (9.8%) | 341 (5.1%) | 163 (2.4%) | 105 (1.6%) | 206 (3.1%) | 2112 (31.6%) |

| Age 61–80 years | 343 (5.1%) | 707 (10.6%) | 431 (6.5%) | 312 (4.7%) | 199 (3.0%) | 478 (7.2%) | 2470 (37.0%) |

| Age 81–100 years | 69 (1.0%) | 175 (2.6%) | 172 (2.6%) | 150 (2.2%) | 113 (1.7%) | 279 (4.2%) | 958 (14.3%) |

| Age 100+ years | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 2 (0.0%) | 2 (0.0%) | 4 (0.1%) |

| Total | 1747 (26.2%) | 1797 (26.9%) | 1031 (15.4%) | 666 (10.0%) | 439 (6.6%) | 998 (14.9%) | 6678 (100.0%) |

Table 3. Most common comorbidities diagnosed in patients with hard-to-heal wounds

| Comorbidities | Patients | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| n=6678 | Percentage | 95% confidence interval | |

| Circulatory diseases | 2534 | 37.9% | (0.368, 0.391) |

| Hypertension | 1542 | 23.1% | (0.221, 0.241) |

| Coronary heart disease | 731 | 10.9% | (0.102, 0.117) |

| Peripheral arterial diseases | 346 | 5.2% | (0.047, 0.057) |

| Peripheral venous diseases | 312 | 4.7% | (0.042, 0.052) |

| Endocrine and metabolic diseases | 2274 | 34.1% | (0.329, 0.352) |

| Diabetes | 1915 | 28.7% | (0.276, 0.298) |

| Hyperlipidaemia | 174 | 2.6% | (0.022, 0.03) |

| Obesity | 125 | 1.9% | (0.016, 0.022) |

| Nervous system diseases | 1786 | 26.7% | (0.257, 0.278) |

| Cerebrovascular diseases | 917 | 13.7% | (0.129, 0.146) |

| Paralysis | 470 | 6.9% | (0.063, 0.075) |

| Peripheral neuropathy | 121 | 1.8% | (0.015, 0.022) |

| Musculoskeletal diseases | 1500 | 22.5% | (0.215, 0.235) |

| Fracture | 422 | 6.3% | (0.058, 0.069) |

| Osteoporosis | 83 | 1.2% | (0.01, 0.015) |

| Respiratory diseases | 1039 | 15.6% | (0.147, 0.165) |

| Pneumonia | 225 | 3.4% | (0.03, 0.038) |

| Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease | 151 | 2.3% | (0.019, 0.027) |

| Digestive diseases | 832 | 12.5% | (0.117, 0.133) |

| Loss of appetite | 101 | 1.5% | (0.012, 0.018) |

| Hepatitis B | 70 | 1.0% | (0.008, 0.013) |

| Genitourinary diseases | 783 | 11.7% | (0.11, 0.125) |

| Chronic kidney disease | 194 | 2.9% | (0.025, 0.033) |

| Blood diseases | 774 | 11.6% | (0.108, 0.124) |

| Anaemia | 303 | 4.5% | (0.041, 0.051) |

The 4931 patients with hard-to-heal wounds, and who were diagnosed with comorbidities, were assessed and classified according to ICD-10. As shown in Fig 3c, 1792 patients were diagnosed with one comorbidity, comprising 26.8% of all cases. Patients with two and three pre-existing comorbidities accounted for 15.4% and 10.0% of the cohort, respectively. Moreover, significant correlation between age and number of comorbidities was found, with older patients having a greater number of comorbidities.

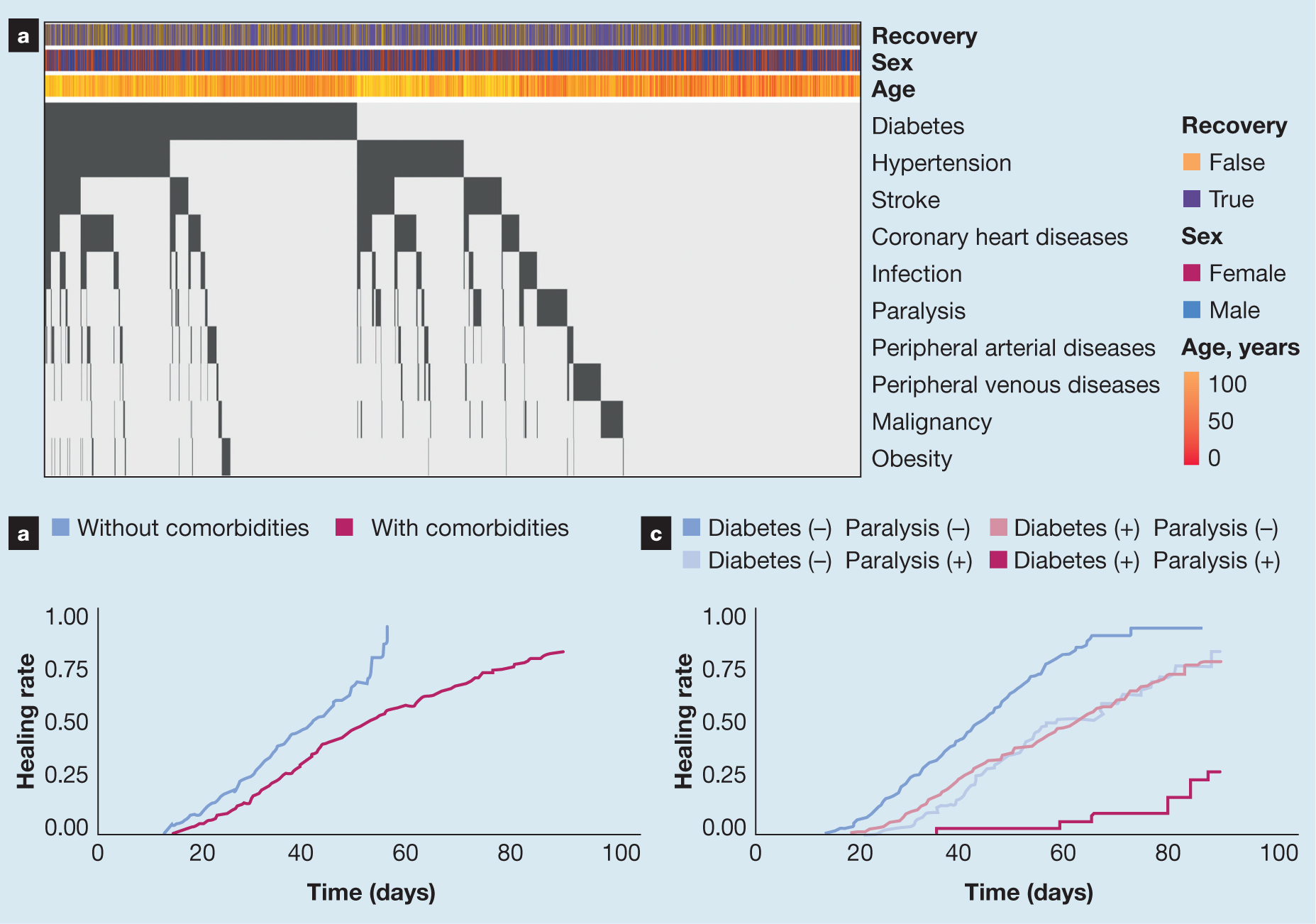

Prognostic factors for wound healing

To explore the prognostic factors for wound healing, 2163 patients were enrolled in further assessment (Fig 4a). During the follow-up period, the median healing time was 51 days, and 52.1% of patients were observed to be healed. The median healing time for patients with and without comorbidities was 54 and 42 days, respectively (Fig 4b). According to previous studies and epidemic statistics, we focused on the effect of common comorbidities on wound healing, including diabetes, hypertension, coronary heart disease, paralysis, peripheral vascular disease, malignancy, infection, stroke and obesity.14,32 As demonstrated in Table 4, several comorbidities, including paralysis, diabetes, infection, peripheral venous and arterial diseases, were significantly correlated with slower wound healing based on multivariate Cox regression. The median healing time for patients with diabetes was 64 days, while the median healing time for patients without diabetes was 45 days (Fig 4c). Paralysis exerted greater influence on wound healing, resulting in a median healing time of 74 days rather than 50 days for other patients without paralysis. Both venous and arterial diseases in peripheral vessels were unfavourable factors for healing hard-to-heal wounds with hazard ratio (HR) values of 0.50 and 0.59, respectively. Infection was an important cause as well as an unfavourable factor for prolonged healing time. Obesity demonstrated significant correlation (HR=0.55; p=0.008) in the univariate model as opposed to the multivariate model (HR=0.70; p=0.127), which resulted from its relationship with diabetes.

Table 4. Multivariate cox regression of hard-to-heal wound healing

| Factor | Hazard ratio | 95% confidence interval | –log P |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years | 1.002 | (0.998, 1.005) | 0.366 |

| Sex: Male versus female | 0.942 | (0.835, 1.063) | 0.478 |

| Diabetes | 0.435 | (0.379, 0.5) | 31.188 |

| Hypertension | 0.747 | (0.643, 0.868) | 3.868 |

| Coronary heart disease | 1.152 | (0.963, 1.379) | 0.917 |

| Paralysis | 0.387 | (0.307, 0.488) | 14.928 |

| Peripheral arterial disease | 0.594 | (0.458, 0.771) | 4.05 |

| Peripheral venous disease | 0.503 | (0.381, 0.663) | 5.961 |

| Malignancy | 1.054 | (0.808, 1.375) | 0.157 |

| Infection | 0.726 | (0.582, 0.907) | 2.319 |

| Stroke | 0.827 | (0.692, 0.989) | 1.423 |

| Obesity | 0.704 | (0.449, 1.105) | 0.895 |

Discussion

This retrospective study collected demographic information and clinical characteristics of patients with hard-to-heal wounds in China. A total of 6678 patients from 552 hospitals located in 30 provinces were enrolled in this study, all of whom had wounds which had been present for >30 days. In these cases, trauma, infection, pressure and diabetes were the four most common causes, and the lower extremities were the most common location. Patients aged 61–80 years accounted for the largest proportion of all cases. Diabetes and hypertension were the most common comorbidities, while diabetes and paralysis exerted the greatest impact on wound healing during the treatment period. The median time of wound healing was 54 and 42 days for patients with and without comorbidities, respectively.

Similar to other epidemiological studies of hard-to-heal wounds in China in recent years, most patients in this study were of older age and had a history of multiple comorbidities and non-traumatic causes, which emphasised that early prevention and diagnosis were of great importance to this high-risk population.7,9 Compared with previous studies, cases of hard-to-heal wounds showed a continuous trend from the younger population to the older population, from external events to systemic factors, and from malnutrition to obesity. In 1995, the median age of patients was 36 years, and most cases of hard-to-heal dermal ulcers were caused by trauma, accounting for 67.5%.6 Moreover, professional distribution showed that farmers and manual workers were the most common occupations in these cases, comprising >60%. In 2007, the 40–60- and 60–80-year-old age groups formed the two largest proportions of all patients with hard-to-heal wounds, comprising 31.2% and 38.7%, respectively.7 Diabetes and trauma became the top causes of hard-to-heal wounds, with proportions of approximately 30% and 20%, respectively. In this study, participants in groups >80 years of age displayed an increased proportion of all cases of hard-to-heal wounds compared with a previous study,7 and groups <40 years of age showed a decreased proportion. Compared with distribution data from 2011,7 the proportion of infectious ulcers has increased from 13% to 23.1%, and the proportion of PUs has increased from 10% to 20.1%. However, the current proportion of diabetic ulcers is 18% lower than that of 2011 levels.7 Our results emphasise that the age of patients with hard-to-heal wounds has increased over the past decades as China becomes an increasingly aged society. Both increased incidence and improved treatment of diabetes contribute to the changed ratio of diabetic ulcers, while the proportion of traumatic wounds has remained at a relatively low level since 2007. Infectious ulcers and PUs have become more common since 1995, which has resulted from the older and more dependent population. The application of new biofilms has been necessary for the better management of infectious ulcers.33 Therefore, changes in epidemiology and aetiology of hard-to-heal wounds bring new challenges to clinical prevention and treatment.

Ageing is one of the most important challenges globally. Age-related skin morphology changes make the skin of older patients more susceptible to damage.34 Furthermore, intrinsic ageing-dependent negative effects on the healing process include inflammatory response alterations, increases in matrix degradation, reduced angiogenic activity and delayed re-epithelialisation.35,36 The clinical consequences of hard-to-heal wounds on the wellbeing of the older population should not be underestimated. Interestingly, hard-to-heal wounds were more common in male patients than female in this study, which is consistent with previous findings.37 Male patients accounted for 60.8 % of all cases and most of them had comorbidities (Table 1). This finding differed from that of a study conducted in 2004, which reported that 41% of patients with ulcers were male and 59% were female.36 Age-related changes in hormone levels, such as oestrogen, androgen and dehydroepiandrosterone have previously been implicated in wound-healing delays in older men.11

Due to the increasing need for attention to be paid to hard-to-heal wounds, we report the prevalence and characteristics of comorbidities in patients with hard-to-heal cutaneous wounds in China. According to ICD-10, about 73.8% of hard-to-heal wound patients are affected by comorbidities and 46.7% have multimorbidity. Increases in medical comorbidities not only induce deterioration, which leads to the under-treatment of wounds and comorbid illnesses, but also negatively impacts self-care, mobility and polypharmacy use. Care should be taken regarding wound management. Specifically, greater attention should be paid to preventing the tearing of skin and fascia, which may involve use of permanent rather than absorbable sutures, maintenance of skin closure for longer than usual, application of proper antibiotic prophylaxis and correction of nutritional deficits.14 The complexity of comorbidities brings many challenges to the treatment of hard-to-heal wounds. Hopefully, the development of multidisciplinary approaches will provide new therapies for patients, especially advanced multifunctional dressing techniques.38 For example, wound dressings with silver or gold nanoparticles exert antibacterial activity and promote wound healing.39

Vascular status was critical for predicting healing outcomes, and peripheral vascular diseases were recognised as risk factors for hard-to-heal wound development.14 This study found that both peripheral venous and arterial diseases were unfavourable factors for wound healing. In addition to reducing wound healing ability, these comorbidities reduced the stress tolerance of patients with hard-to-heal wounds, reducing their ability to cope with infection, surgery and trauma. Thus, special attention must be paid to pain relief and perioperative management in these patients, and minimally invasive methods, both surgical and anaesthesiologic, should be considered.

The most recent epidemiological study of patients with hard-to-heal wounds revealed that the prevalence of diabetes in China was 11%,40 indicating that the prevalence of diabetes in patients with hard-to-heal wounds was nearly three times that of the total population. Diabetes was also identified to be one of the most important factors indicating a prolonged healing process. Diabetes is associated with impaired wound healing and increased susceptibility to hard-to-heal wounds. The prevalence of diabetes has been rising, as has the prevalence of hard-to-heal wounds.41 Available evidence indicates that diabetes medications, such as insulin and metformin, have the potential to prevent wounds from becoming arrested in the inflammatory stage of healing and promote wound healing, independent of their marketed insulinotropic effects.21

Limitations

A major limitation of this study is that information on clinical cost and medical treatment was unavailable, because both inpatient and outpatient cases were included, which introduced many confounding factors. These shortcomings can be remedied in future research by control of irrelevant variables.

Despite this inherent limitation, this study provided a detailed overview of the prevalence and prognosis of hard-to-heal wounds with comorbidity aggregations in China. Possible influences of the pathological state of affected patients on wound treatment processes were considered to guide the management of patients with hard-to-heal wounds. As a result, we suggest that care should be used when selecting an anaesthesia method, pain relief, use of cardiovascular drugs etc. The results of this study may be used to improve clinical management plans to treat patients with hard-to-heal wounds.

Conclusion

Our study revealed that hard-to-heal wounds were most common in the older population with complex comorbidities in China. With the emerging evidence, infection and pressure play more important roles than previously thought in the occurrence and development of hard-to-heal wounds. Diabetes and hypertension were identified as the most common comorbidities, while diabetes and paralysis exerted the greatest impact on the healing process, which should be taken into consideration for the prevention and treatment of hard-to-heal wounds. Our study provided insight into the contribution of each major comorbidity to the outcome of hard-to-heal wounds. We believe it was of value in developing new strategies and in improvement of treatment.

Reflective questions

- What is the recent trend in the population susceptible to hard-to-heal wounds?

- What is the correlation between comorbidities and development of hard-to-heal wounds?

- What roles do comorbidities play in the healing process of hard-to-heal wounds?