Hard-to-heal (chronic) wounds are a growing global health concern. In Europe, the number of patients with acute or hard-to-heal wounds is estimated to be 1.5–2.0 million.1 In the US, hard-to-heal wounds affect approximately 6.5 million people at any one time.2 In China, patients with hard-to-heal wounds accounted for 1.7‰ of the total number of hospitalised patients.3 These data demand that we pay greater attention to wound problems. The pathogenic factors involved in wound healing are changing, and their treatment becoming more challenging. With increasing ageing populations, hard-to-heal wounds such as pressure injuries, vasogenic wounds and diabetic ulcers have become a growing problem.

In general, there are three key goals of wound treatment: removal of the necrotic tissue; control of infection; and tissue regeneration. For hard-to-heal wounds, each treatment step can be difficult. At present, local therapy is the mainstay of wound care, and local treatment combinations, such as CXCR4 receptor inhibitor combined with growth factors, are showing great promise.4

Moist exposed burn ointment (MEBO) is a compound ointment that mainly contains Rhizoma coptidis, Cortex phellodendri, Radix scutellariae and Lumbricus terrestris (earthworms). The current standard of care defines the optimal environment for wound healing as a moist environment.5 As carriers, the propolis and sesame oil in MEBO not only bring nutrition to the wound surface but also create a moist healing environment.6 As a drug developed for burn and scald injury, MEBO has been proven to be effective in treating many types of wounds, such as diabetic ulcers, pressure ulcers and hard-to-heal wounds.7,8,9 It is antibacterial and acts by liquefying necrotic tissue, promoting tissue regeneration, and detoxifying, and its antiphlogistic and analgesic effects have also been reported.10,11,12,13,14 To further improve the efficacy of MEBO, research is emerging on the use of MEBO in combination with other drugs. However, residual ointment on the wound surface often impedes the effect of the treatment. Therefore, under the premise of ensuring the safety of MEBO, it is important to find a combination that can eliminate exudate and accelerate wound healing.

There is a long history of maggot use in the treatment of wounds. Maggot therapy has experienced a renaissance, coming back into clinical practice in the early 20th century,15 and live maggots are used to treat hard-to-heal wounds.16,17,18,19,20 A previous study found that maggots had >10 clinical effects, mainly antibacterial activity, antibiofilm activity, anti-inflammatory activity, fibroblast migration/proliferation, neurogenesis and proangiogenic activity.21 Additionally, living maggots have the unique function of eating necrotic tissue to achieve debridement.22 With good curative effects and low side-effect risks, this medicine has been recognised and promoted by an increasing number of clinicians.23

To date, both laboratory and clinical studies have yielded fruitful results. However, further study of the culture and preparation of maggots is still required.24 In addition, supplementary medicine during the preparative and interval periods of maggot therapy is extremely important. Research results have shown that many topical medicines were deadly to maggots, so choosing a drug that worked in concert with maggot therapy is essential.25

The combination of MEBO and maggot therapy is theoretically possible. They both originate from and are superior to traditional Chinese medicine (TCM). MEBO is a modern compound ointment containing TCM ingredients, while maggot therapy could be regarded as an external application within TCM. First, in TCM it is thought that when herbs are ineffective for intractable diseases, medicine derived from animals may have better therapeutic efficacy. Interestingly, the earthworms in MEBO and maggots are both related to animal medicine. Second, as a result of their wriggling and crawling action, maggots could remove the ineffective residual ointment from the wound. Third, MEBO and maggots have a similar therapeutic mechanism, including removing necrotic tissue and promoting granulation. This suggests that a combination of MEBO and maggot therapy may be a whole-course treatment choice for wound healing. Therefore, it is important to clarify the safety and efficacy of the combined application of MEBO and maggot therapy in wound healing.

To better understand the interaction between maggots and MEBO, a simple coexistence experiment was performed to determine the survival condition of maggots in MEBO. Then, a series of patients received a combination of MEBO and maggot therapy, are reported for the first time.

Methods

This study consisted of one laboratory-based coexistence experiment and a case series report, which were performed at the First Affiliated Hospital of Dalian Medical University, People's Republic of China. The coexistence experiment was a simple experiment to verify whether or not maggots could survive in MEBO. The case series was used to show the clinical therapeutic effect. The change in wound area was observed by the transparency method.26 The patient's pain was recorded by using the visual analogue scale (VAS).

Ethical approval and consent to participate

The patients included in this article provided written informed consent to receive the combination therapy and to publish their case details, including photographs. This study was assessed and approved by the Ethics Committee of the First Affiliated Hospital of Dalian Medical University (approval number: YJ-KY-2019-65).

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS 17.0 software (SPSS, Inc., US). Comparisons between groups were conducted using survival analysis. The Kaplan–Meier method was used to draw the survival curve and the log-rank test was used for univariate analysis. A p-value of ≤0.05 was considered to indicate a statistically significant difference.

Coexistence experiment

The larvae of Lucilia sericata was used for both the coexistence studies and the case series. Artificial breeding was carried out after wild collection and identification. The double disinfection method of eggs and bodies was used for maggot sterilisation.27 A total of 60 first-instar larvae that had just hatched from eggs were selected carefully, and randomly put into six bags (approximately 3cm×3cm, each containing 10 maggots), which were made of polyamide. The specification was 120 mesh. All larvae were healthy and energetic. The maggot bags were randomly divided into two groups:

- MEBO group (MEBO+maggot)

- Control group (maggots only).

The maggots were kept at room temperature, at 100% humidity and in the dark. Normal saline gauze was placed under the maggot bags in the control group, while approximately 0.4g MEBO (Chinese State Medical Permitment number: Z20000004; Shantou MEBO Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd., China) was added to the normal saline gauze in the MEBO group. Then, the number of live maggots was counted once a day until all of the maggots died. When the quiescent time exceeded one minute, the maggot was presumed dead.

Case series

All of the patients were treated in the outpatient clinic. Before wound treatment, the treatment methods were introduced to the patient and their family members, and the treatment plans were selected according to the changes in the wound and the wishes of the patient and their family members. In this report, we selected seven patients who were willing to receive the combination therapy and to have their case information published. There were two forms of the combination therapy, which were selected according to the condition of the patient's wound:

- Maggots were simultaneously used in conjunction with MEBO

- MEBO and maggots were used sequentially.

We used maggot therapy at a standard of 10–15 maggots per square centimeter. The patients did not receive antibiotics during wound treatment, and were monitored for changes in temperature and laboratory tests, such as bacterial culture, were also carried out.

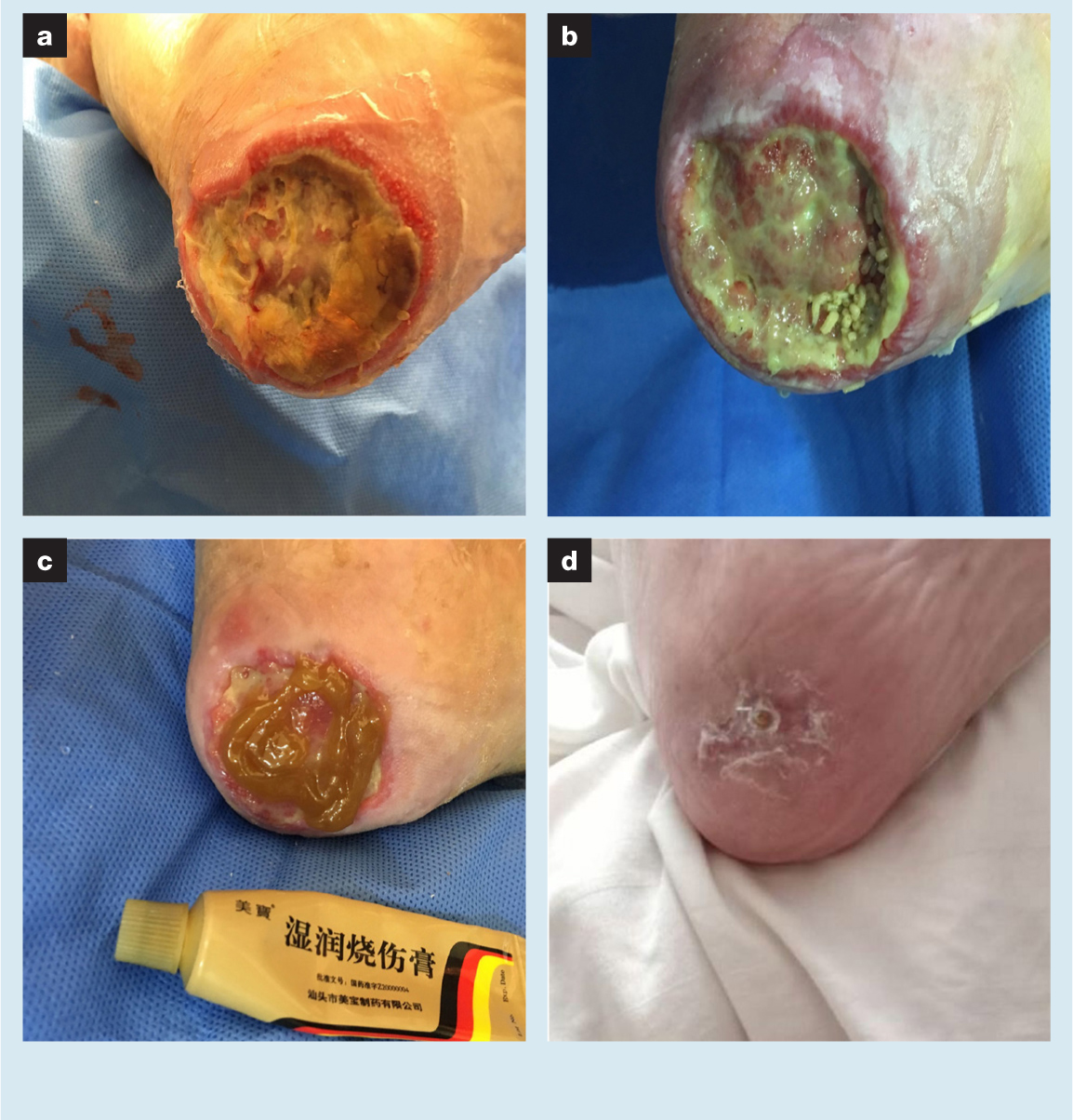

Case 1

A 57-year-old male patient had a scar ulcer on the medial margin of the right foot (VAS score 2) (Fig 1). The patient complained that the wound was caused by scratching because of skin itching. The wound recurred once a year, and disinfecting agents, such as povidone iodine solution, helped to gradually heal it each time. This went on for nearly two decades. The patient first came to the clinic in 2019. In the past, he had been treated in several hospitals for periods of more than a year, including antimicrobial treatment, photophysiotherapy and folk prescriptions, but the wound did not heal. The patient reported having been diagnosed with scleroderma a decade earlier. He had not received any medical treatment for scleroderma, and there was no scleroderma-related disease other than the wound. He denied any history of other illnesses. X-rays showed no bone damage and bacterial culture found Acinetobacter baumannii.

Pigmentation and desquamation in the right foot were obvious. Skin sensation, activity and the peripheral blood supply were good. Without any fresh granulation tissue, there was a small amount of necrosis in the relatively dry wound. The skin at the wound edge was hard in texture, and slightly red and swollen. Limited debridement was chosen, and MEBO was applied to the wound and the surrounding skin. At one month later, the wound became wet and suitable for maggot therapy. Following simple wiping, a customised maggot bag was placed on the wound. After two consecutive maggot therapies, the necrotic tissue on the wound was almost cleared and fresh granulation tissue grew rapidly (VAS score 2). MEBO was then selected for continuous use. At two weeks later, the rate of re-epithelialisation slowed significantly, and the growth of granulation began to cease. Punctate cutaneous implantation was performed on the wound, and then MEBO was used again. The total duration of treatment until healing was 25 weeks. The scope of the new scar was limited, the appearance was good, and the motor function was largely preserved (VAS score 0).

Case 2

A 96-year-old bedbound female patient had pressure ulcers (PUs) on her left heel for >1 month (VAS score 0) (Fig 2). The patient was intolerant to pain, so the initial clinician only performed negative pressure wound therapy (NPWT) on the diseased foot. However, after one month, the wound had not significantly improved. The patient had a history of heart disease, high blood pressure and osteoporosis, and took the corresponding oral medications. The relatives of the patient came to the outpatient clinic to obtain for further diagnosis and treatment for the patient. Bacterial culture indicated Pseudomonas aeruginosa.

The necrotic tissues in the wound mainly included inanimate fascia and liquefied adipose tissue. The skin at the edge of the wound had a marked inflammatory response. A foul odour emanated from the wound and may have been related to the long periods of NPWT. Limited debridement and repeated rinsing were used to clean the wound. Then, first-instar larval maggots were directly installed in the wound in which a layer of MEBO had already been placed. The dressing ensured humidity within the wound. The stress injury of the diseased foot was relieved. During this time (about one month) only maggots were used for treatment. The patient did not complain of any pain or discomfort (VAS score 0). The necrotic tissue of the wound was gradually cleared away while fresh granulation began to grow. MEBO gauze was used and applied to the wound twice a day. During this period, NPWT was also used for two weeks to stimulate granulation growth. After 12 weeks, the heel PU had healed completely (VAS score 0).

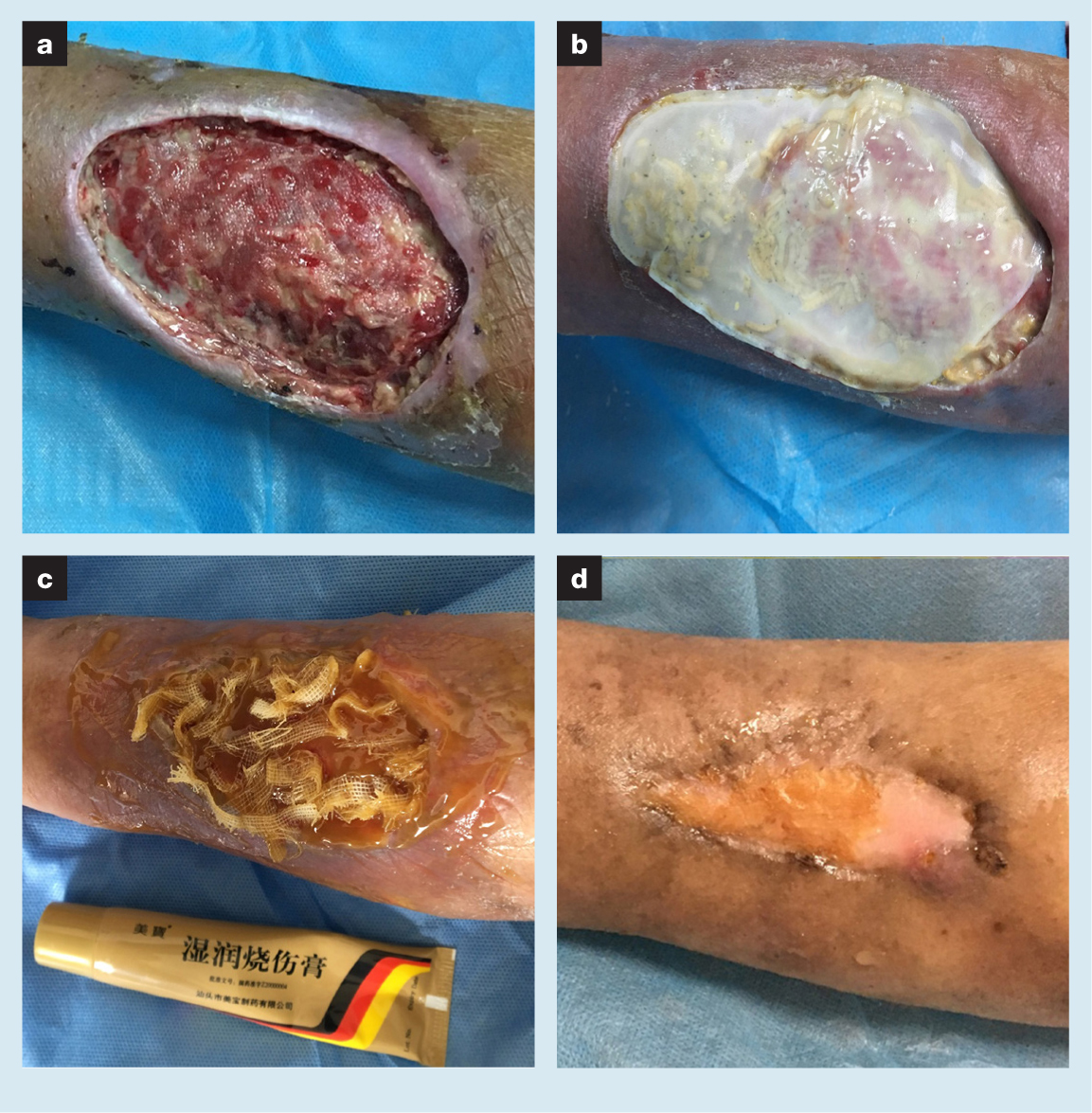

Case 3

A 73-year-old female patient had a left forearm dorsal skin defect wound (VAS score 2) (Fig 3). The patient had a left fracture of the distal radius in 2018. Although the fracture had already healed via conservative treatment, forearm muscle pain caused by plaster external fixation was a constant concern for the patient. Therefore she frequently massaged the muscles. A large subcutaneous haematoma unexpectedly developed on her left forearm. For a number of reasons, including misdiagnosis, the haematoma did not receive effective treatment or adequate attention. Gradually, the haematoma separated the skin from the subcutaneous tissue and the increased ischaemia led to gangrene of large areas of the skin. The subcutaneous haematoma was caused by the patient's anticoagulant therapy. The patient had been treated with oral warfarin for pulmonary embolism for a long period of time. After the subcutaneous haematoma manifested, her oral medication was changed to rivaroxaban in the respiratory outpatient clinic. Other underlying diseases were not noted. The lesion persisted for five weeks. This patient first came to the outpatient clinic in early 2020. The culture result of the wound exudates showed the presence of Staphylococcus epidermidis.

A large black scab was removed from the left forearm by scissors, and full-thickness skin necrosis was evident. The soft tissues above the deep fascia had been lost and the wound was interspersed with a moderate amount of necrotic tissue and a small amount of old granulation tissue. The skin at the wound edge had become thinner and was separated from the subcutaneous tissue. Local inflammatory response was not obvious. Repeated rinsing was undertaken to clean the wound during treatment. Then, MEBO was used to infiltrate the medicinal gauze strips that were placed loosely on the surface of the wound. At the same time, the wound morphology was recorded by the transparency method to assist in completing the production of the customised maggot bags. A week later, the wound under the dressing was stable, without progressive tissue necrosis or aggravation of the infection. The customised maggot bag was placed on the wound. Maggot therapy to remove necrotic tissue from the wound and stimulate growth of fresh granulation was performed for a total of three times. During the treatment, the patient complained of tolerable forearm pain (VAS score 5). Subsequently, MEBO and NPWT were used to complete the remaining wound repair work. The forearm pain was relieved by MEBO. After seven weeks of treatment, the wound was completely healed. During the wound treatment process, the patient was required to perform functional exercise. At the end of the treatment, her ability to move her wrist and elbow was good (VAS score 0).

Case 4

An 82-year-old male patient presented with a right heel iatrogenic incision nonunion combined PU (VAS score 0) (Fig 4). At 2.5 months previously, the patient suffered 12 fractures, including fractures of the bilateral calcaneus, left ankle, left tibial plateau because of accidental falls. Due to limited activity, stress was concentrated in the heel and finally led to a PU. Open reduction and internal fixation of fractures in eight places were performed in the operating room. At two months after surgery, the incision in the left heel had failed to heal. A second operation was performed to remove the internal fixation, perform debridement and attain direct incision closure. Unfortunately, 2.5 months later, the incision had formed a deep sinus tract with extravasation. Due to the severity of the trauma, the patient was confined to bed. The patient's relatives came to the outpatient clinic, hoping to solve the problem of the heel wound. The patient was previously healthy and had no other diseases.

Surgical exploration and debridement was performed under local anaesthesia. During the operation, the sinus tract and necrotic tissue of the PU were excised. The debridement depth was approximately two-thirds of the long axis of the calcaneus. A large number of dead bones and inflammatory granulation were removed. The nonunion aspect may therefore have been related to allograft bone implantation. The wound was then irrigated with normal saline. Bacterial culture of the secretions showed the presence of Staphylococcus epidermidis. A dressing change with MEBO was applied to the wound to stabilise the wound edges. A week later, free-range maggots were selected and placed into the wound for three days of treatment. When the dressing was opened again, the maggots were much fatter than at the beginning of the When the dressing was opened again, the maggots were much fatter than at the beginning of the treatment. The area of bone defects in the wound had obvious changes with granulation growth (VAS score 0). Subsequently, MEBO, maggot therapy and NPWT were used alternately. In the later stage of treatment, the wound skin hardened and scarring was obvious, and so a secondary debridement was performed. Maggot therapy was used in combination with MEBO postoperatively to create fresh wound edges and stimulate tissue growth. Complete closure of the wound was achieved after 37 weeks of treatment (VAS score 0).

Case 5

A 77-year-old male patient had a right diabetic foot ulcer (DFU) (VAS score 3) (Fig 5). Approximately one year previous to presentation at our clinic, due to unknown reasons, the patient developed gradual darkening of the skin of the great toe of the right foot with pain, redness and swelling of the first metatarsophalangeal joint. Surgery was performed to amputate the right great toe in another hospital. However, there was no healing trend and the second toe also showed changes including a decrease in skin temperature and darkening of the skin. At two months post-surgery, the patient underwent right lower limb arterial interventional surgery. Although the right anterior tibial artery was recanalised, the response to treatment with routine iodophor dressing changes was still not effective. At the consultation in the Department of Cardiology, the patient's wound began to be treated effectively in clinic. The patient had a history of diabetes for >20 years and had several other illnesses, including atherogenic occlusion of the lower limbs, heart failure, coronary atherosclerosis, high blood pressure, anaemia, hypoproteinaemia and bilateral pleural effusion. Insulin, erythropoietin, diuretics, antihypertensive drugs and lipid-lowering medications were used in the treatment of these diseases.

Swelling of the right lower limb was evident. The skin temperature was slightly cold and dorsal foot artery pulses were not palpable. Additionally, skin sensation was reduced but motor function was not seriously affected. Pigmentation of the dorsal foot was obvious. There was no tenderness or abscess fluctuation seriously affected. Pigmentation of the dorsal foot was obvious. There was no tenderness or abscess fluctuation of the soles. Thin black scabs appeared on the tip of the second toe. The patient's wound contained a large volume of secretions. Necrotic fat, fascia and tendons were attached to the wound. The first metatarsal bone was exposed. There were a small number of old granulomas upstream of the wound. During flushing and probing of the wound, numerous tissue defects near the bottom of the foot were found. Limited debridement was then performed, and MEBO was applied to the wound and the tip of the second toe. Maggots were placed on the wound two days later for a period of four days. Maggot therapy was deemed valid because the necrotic tissue in the wound had been cleaned (VAS score 2). At the same time, the swelling of the right lower limb was improved after position management. Pleural puncture drainage and protein supplementation therapy had a beneficial role in reducing the symptoms of heart failure and limb swelling. To further facilitate swelling reduction and drainage of the wound, NPWT was then used for two weeks. After the swelling of the limb and wound subsided, MEBO and maggot therapy were used alternately. The DFU was gradually filled with granulation and re-epithelialisation was eventually completed (VAS score 0). Total treatment duration was 23 weeks.

Case 6

A 42-year-old male patient presented with a right tibia anterior skin ulcer (VAS score 3) (Fig 6). The cause was necrosis of the skin tissue caused by a collision injury at a building construction site. Then, an ellipsoidal ischaemic area appeared on the right lower leg and became gradually shrivelled and extravasated purulent fluid. Local eschar was cleared at another hospital one month previously and had formed a wound. No improvement was observed after routine dressing change. The patient presented at our outpatient clinic for diagnosis and treatment. There was no previous history of other diseases.

A small amount of necrotic tissue remained in the wound, the edge presented a cliff-like shape, and up to 3cm of the surrounding skin was dark red. Additionally, there were some latent areas below the edge. Large amounts of normal saline were used to flush out the wound. Eye scissors were used to remove some of the necrotic tissue. A routine maggot bag was then applied to the surface of the wound. After nine days of maggot therapy, fresh granulomas sprouted and replaced the dead subcutaneous tissue. Moreover, the degree of inflammatory response in the wound was significantly improved. Granulation tissue had a tendency of spreading and growing inward along the wound edge skin. During maggot therapy, the patient felt more pain (VAS score 5). Dressing changes with MEBO further assisted wound healing and pain symptoms relieving. After two months of treatment, the skin ulcer of the right tibia anterior was finally healed (VAS score 0).

Case 7

A 50-year-old male patient had an infected skin ulcer on the anteromedial region of his right tibia (VAS score 2) (Fig 7). At six months previously, the patient was accidently stabbed while chopping wood. Subsequently, signs of infection including pain, redness and swelling began to appear in his right calf. Continuous intravenous antibiotic therapy suppressed the infection but local tissue necrosis was not reversed. Over time, the necrotic tissue shrivelled and became more well defined. Then, debridement was performed in a village clinic to remove the eschar. However, a subsequent conventional dressing change with povidone iodine solution could not effectively reduce the remaining necrotic tissue, and there was no wound healing trend for two months. The patient reported that he had venous disease of the lower extremity, but provided no exact details.

The first impression of this wound was that the edge was hard. Medium amounts of necrotic tissue and little fresh granulation tissue were found in the wound, as well as a mild inflammatory response. With large areas of pigmentation, the skin around the wound may have developed some degree of fibrosis following the previous inflammatory response, which would hinder wound healing. Normal saline was used to flush out the wound. The edge was then marked using the transparency method. MEBO was applied to the wound and gauze strips were placed to facilitate drainage. A customised maggot bag was used to cover the wound two days later. The maggot therapy lasted for three days in order to carry out its biological debridement function. When the dressing was removed, the necrotic tissue in the wound was cleaned up. Granulation growth and re-epithelialisation were gradually completed via MEBO dressing changes. After three months, the wound was completely healed (VAS score 0). The patient did report aggravation of pain (VAS score 5) during the maggot therapy period but this was eased by the MEBO.

Results

Coexistence experiment

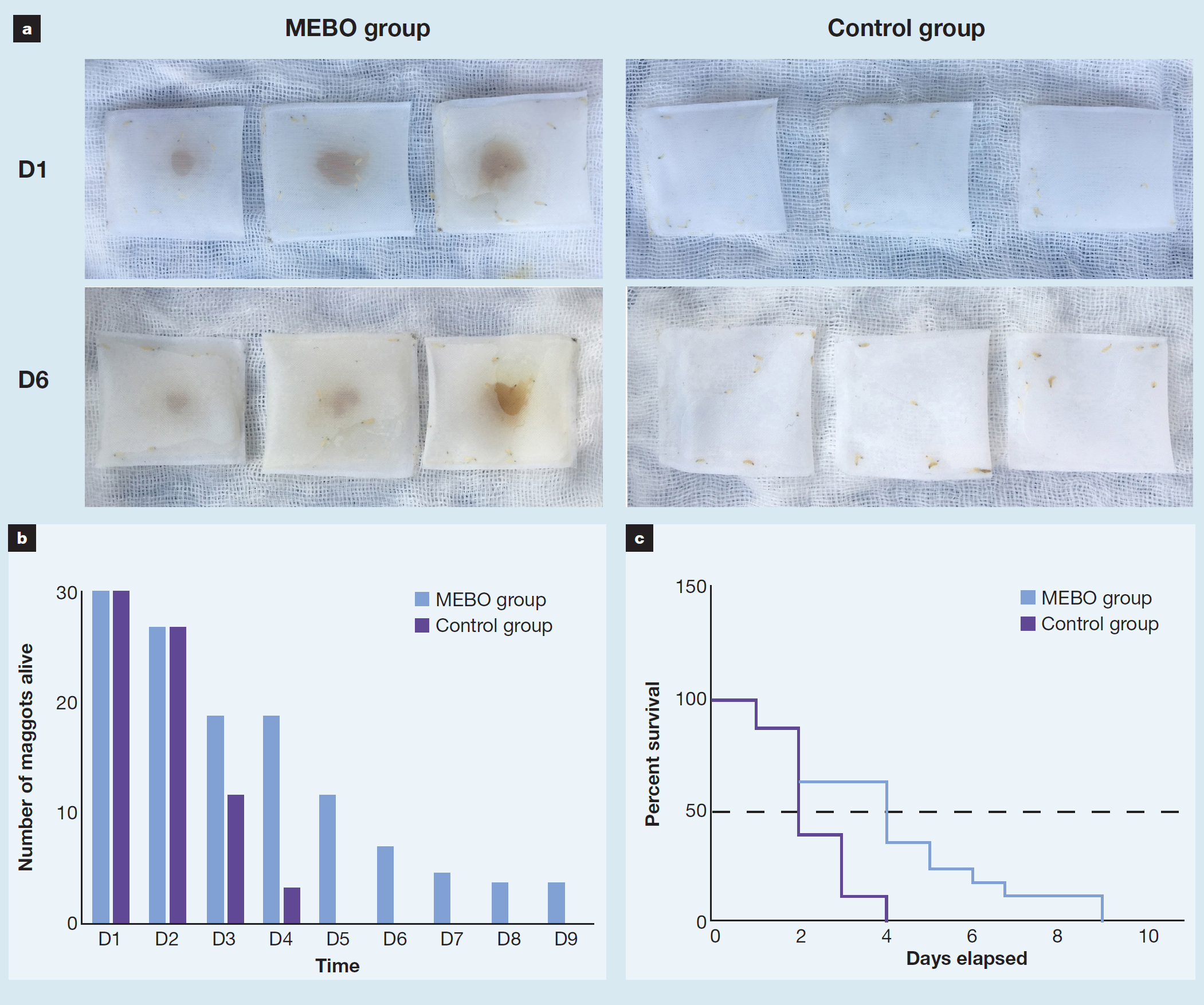

On the first day of the coexistence experiment, the viability of maggots in the two groups was good, and there was no difference in their survival numbers (Fig 8a). From the third day, the difference in the number of surviving maggots between the two groups changed. In the MEBO group, the number of survivors in the three bags was 5, 6 and 8, respectively. However, those in the control group were 3, 5 and 3, respectively. The number of live maggots in the control group was significantly reduced. The maggots in the control group were all dead by the fifth day, and the longest surviving maggot lived for nine days in the MEBO group (Fig 8b). The survival analysis showed that the median survival time in the MEBO group and control group was four days and two days, respectively. The survival curves were significantly different between the MEBO group and the control group (p<0.05) (Fig 8c). That was, MEBO might allow maggots to survive longer than with normal saline alone.

Case series

The general characteristics of the patients is shown in Table 1. Of the seven patients, five were male and two were female, ranging in age from 42–96 years. Wound duration before treatment ranged from 4–48 weeks. All patients' wounds met the criteria of being a hard-to-heal wound and were located in the foot (n=4), in the lower leg (n=2), and the forearm (n=1). All patients received combination therapy, with a treatment time spanning from 7–37 weeks. During the treatment process, four patients received NPWT, while one patient received punctate cutaneous implantation. Additionally, most patients underwent basic debridement of the wound. In terms of side-effects, three patients complained of pain: one case occurred in the forearm and two cases occurred in the lower leg. With combination therapy, all of the wounds eventually healed.

Table 1. Overview of case series

| Case No. | Age, years | Sex | Wound type | Wound duration, weeks | Wound region | Combination therapy use | Additional treatment | Treatment duration, weeks | Side-effects | Curative effect |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 57 | M | Scar ulcer | 48 | Medial margin of the right foot | MEBO+maggot bag+MEBO | Limited debridement, punctate cutaneous implantation | 25 | No | Completely healed |

| 2 | 96 | F | PU | 4 | Left heel | Free-range maggot+MEBO | Limited debridement, NPWT | 12 | No | Completely healed |

| 3 | 73 | F | Skin necrotic wound | 5 | Left forearm dorsal region | MEBO+maggot bag+MEBO | Debridement, NPWT | 7 | Pain | Completely healed |

| 4 | 82 | M | Iatrogenic incision nonunion combined PU | 10 | Right heel | Alternate use of MEBO and free-range maggot | Debridement, NPWT | 37 | No | Completely healed |

| 5 | 77 | M | DFU | 48 | First metatarso-phalangeal joint of right foot | Free-range maggot+MEBO | Limited debridement, NPWT | 23 | No | Completely healed |

| 6 | 42 | M | Traumatic skin ulcer | 4 | Right tibia anterior region | Maggot bag+MEBO | Limited debridement | 8 | Pain | Completely healed |

| 7 | 50 | M | Infective skin ulcer | 8 | Right tibia anteromedial region | MEBO+maggot bag+MEBO | None | 12 | Pain | Completely healed |

No.—number; MEBO—moist exposed burn ointment; PU—pressure ulcer; NPWT—negative pressure wound therapy; DFU—diabetic foot ulcer

Discussion

The serious consequences caused by wounds are self-evident, such as systemic infection, limb necrosis, dyskinesia, and even death. The increasing ageing population and the diversity of injury-causing factors, as well as the underlying diseases and pathogenesis of patients seriously affect wound treatments. With the application of antibiotics, the emergence of specialised dressings and new wound medications, wound therapy entered a new historical moment. However, their application has challenges, including antibiotic resistance, ineffective treatments and side-effects. The search for safer and more effective treatments continues. Compared with new wound therapy drugs, traditional approaches may have some advantages. TCM and other traditional medicines, such as maggot therapy for removal of necrotic tissue and granulation promotion, could solve the problem of hard-to-heal wounds.

Maggot therapy used in medicine is a paragon of biological intelligence. Its safe antibacterial action, specificity in removing necrotic tissue, and highly effective stimulation of tissue growth are unique advantages in the promotion of wound healing. The antibacterial action of maggots is related to their direct phagocytosis of bacteria and their secretion of antibacterial peptides.28,29 Necrotic tissue is consumed as food by maggots.22 In addition, maggots may also secrete enzymes for necrotic tissue digestion.30 At present, maggots are known to mainly promote wound healing by their secretions.31 The specific mechanism may be related to the regulation of signal transduction pathways. By upregulating of c-Myc, VEGF, and cyclin D1, TGF-beta/Smad3 and STAT3 signalling may play an important role in maggot promoting wound healing.32

A large number of clinical studies have confirmed the reliability of maggot therapy.33,34,35 Maggots can play an important role in treating wounds when conventional treatment has failed.35,36 It is noteworthy that this treatment is also effective for burn wounds.37,38 Meanwhile, the larvae usually cost approximately $100 USD per vial, making it a cost-effective treatment.39 Great progress has been made in the use of maggot therapy, which has developed into two forms: free range (where the maggots are not confined and can move freely over the wound); and maggot bag treatment (where the maggots are secured in a fine mesh bag but are still able to access to the wound).21,22 The timing of maggot therapy has also changed. Maggots are now used not only during debridement but also to stimulate granulation growth.40 The concept of combination therapy with maggots has already been proposed.41 Even more exciting combination therapy involving maggot therapy combined with disinfectant or special dressings has been practised in clinical practice.42

However, the practical problems of maggot therapy are still numerous. For cases with multiple wounds, maggots can only be used for the treatment of the main wound, while treatment options for other adjacent, more shallow wounds appear to be limited. The main reason for this is that maggots are easily affected by drugs applied to adjacent wounds and die, affecting the treatment effect on the main wound.24,25 The preparation period of maggots is often not fixed, and patients who need maggot therapy often have to wait for 2–4 days or longer. The smell during maggot therapy can have a negative impact on the patients' psychology and cause other problems in daily living, such as attracting other insects. A suitable drug to neutralise the odour will also reduce the psychological burden on patients. If free-range maggot therapy is used, the larva can quickly escape to the external environment. If maggots can be temporarily confined to the wound, this will ease their use. Using a maggot bag may be a good option for limiting the maggots, but it also loses some of the ability for free debridement, especially for wounds with uneven surfaces. In the later stages of wound healing, the treatment effect of maggots is no longer obvious. Drugs that can be used to complete re-epithelialisation could be a substitute. Therefore, drugs that can be used in conjunction with maggot therapy are urgently needed.

MEBO can be applied during all stages of wound treatment. It comes from TCM and has been much used in the clinical treatment of burn wounds. MEBO debridement is achieved by liquefying necrotic tissue.11 The ointment has certain bacteriostatic effects on a few species of bacteria.10 The core mechanism of MEBO in wound healing is tissue regeneration.14 As a nutrient, MEBO nourishes stem cells in tissues and accelerates their differentiation, thus promoting wound repair and healing.43 Studies have shown that, from a molecular point of view, this process works by activating signalling pathways.7 MEBO has been used in the treatment of hard-to-heal wounds for many years, and animal and clinical studies have demonstrated its efficacy in the treatment of hard-to-heal wounds.7,8,9 It is also safe, without obvious side-effects.44,45,46 Additionally, a number of other treatment options have been tried in combination with MEBO, for example ionic silver dressings, with good results in the treatment of acute anal fissures, aplasia cutis congenita and burn wounds.47,48

Nevertheless, there are also some problems with the use of MEBO that urgently need to be solved. First, an MEBO dressing change is simple but not convenient to use. Changing dressings 4–6 times a day will produce a huge burden on health systems and patients. How to reduce the workload caused by numerous MEBO dressing changes is worth further research. Second, at the time of dressing replacement, the liquid containing the necrotic tissue may accumulate in the ravines of the wound and be difficult to drain. In this case series, the MEBO was difficult to rinse out, even with large quantities of saline. Therefore, it is also necessary to find an effective way of removing any residual liquid. For MEBO, which relies more on the self-potential of patients to heal, a combination of drugs that enhance its therapeutic mechanism may be beneficial to promoting effective wound healing. This is consistent with the widely accepted strategy of a multimethod combination therapy for wound healing.

In the context of both clinical practice needs and theoretical similarity, a simple coexistence experiment was carried out. The results were as expected and provided a basis for combining the two treatments. Maggot survival was better in the MEBO group than in the control group, and the difference was statistically significant (p<0.05). This showed that MEBO had no toxic side-effects on maggots. Some of the ingredients in the ointment may even be a temporary food source for maggots. In the clinical case series, seven patients with hard-to-heal wounds were selected to receive application of the combination therapy of MEBO and maggots. The cases included scar ulcer wounds, necrotic ulcer wounds, PUs, DFUs and mixed wounds. In the course of treatment, and in accordance with the specific situation of the wound, we chose different combinations of MEBO and maggots. These results suggested that MEBO could be used for the preparation period of maggots and also become a suitable follow-up treatment after maggot therapy. In the past, before applying maggots, irritants or specific drugs could not be used on the wound. There was also no suitable combination of drugs for follow-up treatment. This is likely to delay the treatment of the wound. MEBO stabilises the wound prior to maggot therapy by softening the necrotic tissue and controlling the infection. It provides good wound conditions and allows time to prepare the maggots for use in the wound. The maggots then remove the MEBO-containing necrotic tissue and begin their own wound healing task. After maggot therapy, advantage could be taken of the re-epithelialisation promoting ability of MEBO for subsequent therapy. This makes MEBO follow-up treatment of wounds a valuable option. MEBO could facilitate the care and treatment of wounds or lesions other than the main wound. Multiple and complex problems with wounds are common. Skin lesions and other minor wounds may accompany the primary wound. MEBO has the potential for the safe use in these wounds due to its mild therapeutic properties while maggot therapy is being applied. In addition, MEBO could be applied in advance to the wound to prevent maggot escape. Due to their peristaltic characteristics, maggots do not easily adhere or fix on a wound. An oily ointment makes it hard for maggots to crawl away from the wound. Without worrying about maggots escaping quickly from the wound, health professionals can select more vigorous larvae for treatment. Under this combination therapy model, the difficulty of adhesion and fixation of free-range maggots would hopefully be solved.

The combination of MEBO and maggot therapy is an innovation of traditional medicine in wound treatment. but their specific mechanism of action should be researched further. Multimodality or combination therapy has become a mainstream form of treatment, while the moist healing theory has become widely accepted. Therefore, simultaneously using MEBO and maggot therapy conforms to the current therapeutic concept. Moreover, MEBO is able to create a local environment for moist healing, in which maggots are also prone to live. As treatments with a strong ability to promote wound healing, these two therapies can be used throughout the wound healing process. Their characteristics are also more natural. The aroma of MEBO can neutralise the smell of maggot therapy.

Treatment with maggots on the lower leg and forearm, where skin nerves abound, may cause or exacerbate pain. Pain after maggot therapy is consistent with previous reports.49 The mechanism that causes pain in the patients is complex and may be related to crawling irritation, bites and the secretions of maggots. In our case series, three patients (cases 3, 6 and 7) had pain or increased pain. This situation was quickly alleviated with subsequent MEBO use. The pain-relieving components in MEBO might play a useful role.

Based on the results of this experimental study, MEBO appears to be harmless to maggots. Thus, the combined use has a certain degree of safety. However, there are a number of questions that need to be further researched. It is not clear whether the combination therapy (MEBO+maggots] is better than either the sole use of maggot therapy or MEBO, or other combinations with include maggots or MEBO. The analgesic effect of MEBO after maggot therapy needs to be investigated in a large study. The results of animal experiments and clinical trials will be helpful to judge the efficacy of this combination therapy. A study of the interaction mechanism between the MEBO and maggots is also needed.

It remains to be seen whether MEBO will merely provide some of the essential material for maggots to survive or whether it will play its own role in promoting wound healing.

Limitations

This study contains some limitations to both the coexistence experiment and to the case series. As far as the current technology is concerned, the index of observation and detection of maggot viability is still rare. We only used observation to determine the survival rate of the maggots. New inspection methods should be developed to judge toxicity of drugs to maggots. The order of application of MEBO and maggot may influence the curative effect. Thereforce, the best pattern of combined application is not certain. The reported cases were of different types of wounds. In the future, it will be much more meaningful to observe the curative effect of the combined application for more similar wounds.

Conclusion

In this coexistence experiment and case series report, we found that MEBO improved the survival rate of maggots and that the seven cases of hard-to-heal wounds included were healed completely. The combined application of MEBO and maggots had no obvious side-effects. It is therefore possible to use them together to promote wound healing. The flexible application of MEBO and maggots may enrich wound treatment methods. Even so, there are still many issues that need further and research, such as curative effect, best pattern of application, and interaction mechanism. Based on our preliminary results, we believe that the combined application of MEBO and maggots is a promising way of promoting wound healing.

Reflective questions

- How could this combination therapy be used more effectively?

- What is the optimal number of maggots that are required for use in this combination therapy?

- How long is the training period for health professionals to learn this combination therapy?